The Trouble with TVPI, DPI, and RVPI

Imagine this you’re an investor sitting in a polished conference room. The General Partner (GP) of a biotech-focused private equity fund is waxing poetic about their fund’s stellar TVPI. “We’ve achieved 2.5x!” they declare, their voice brimming with pride. A slide appears on the screen, showcasing a tidy bar chart with climbing numbers. You sip your coffee, impressed, and perhaps a little envious. But should you be?

The reality of private equity metrics—Total Value to Paid-In Capital (TVPI), Distributed to Paid-In Capital (DPI), and Residual Value to Paid-In Capital (RVPI)—is that they often tell an incomplete, if not misleading, story. Like a magician’s sleight of hand, these numbers distract from the messier truths of risk, timing, and uncertainty. And let’s not forget, they’re self-reported. Yes, you heard that right: the GP gets to write their own report card.

A Personal Tale of Metrics in Action

Meet Sisko, a Limited Partner (LP) who recently invested in BioVenture Fund I, a biotech fund with an ambitious mandate to tackle rare diseases. Sisko was drawn to the fund’s promise of double-digit returns, buoyed by its glowing metrics. At the fund’s two-year update, he was presented with the following numbers:

- TVPI: 1.5x

- DPI: 0.1x

- RVPI: 1.4x

The GP assured Sisko that the fund was performing exceptionally well. “We’ve already returned 10% of your investment, and the rest is on track to deliver!” But Sisko, being a skeptical sort, dug deeper.

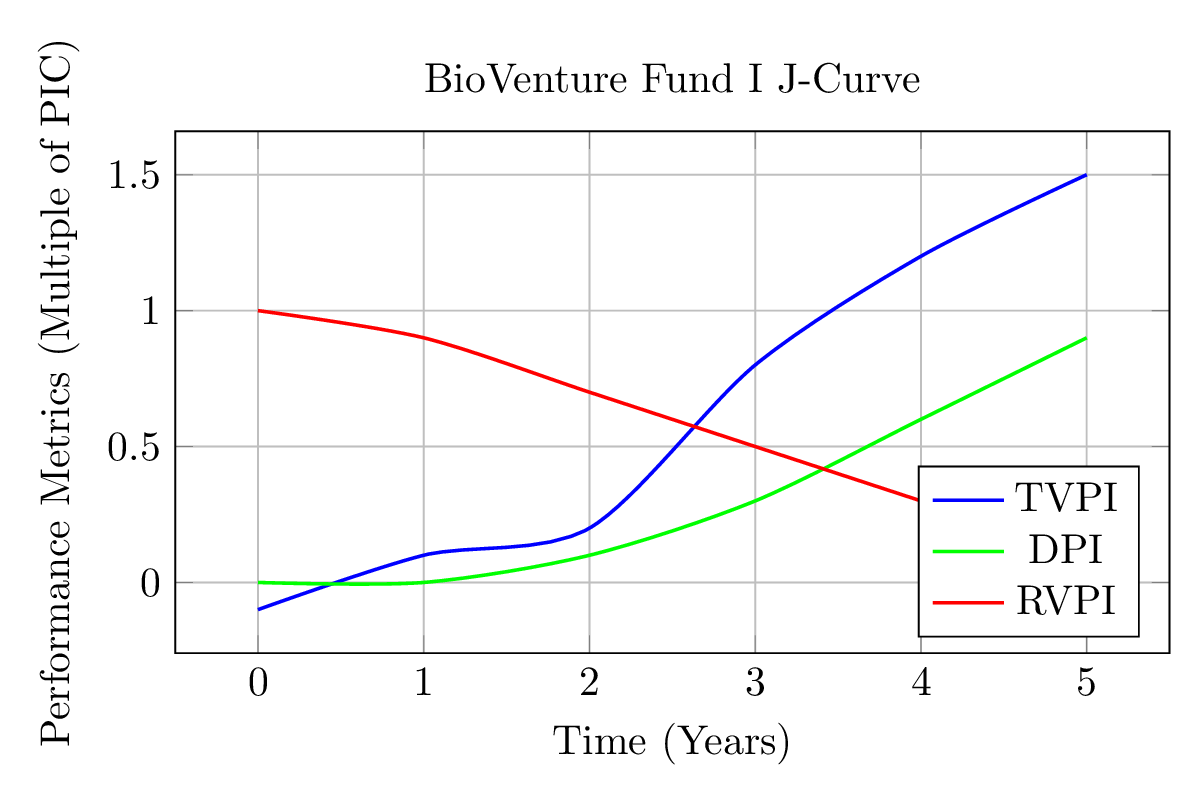

The J-Curve: A Familiar Tale of Peaks and Valleys

The GP’s rosy outlook didn’t align with the notorious J-curve, a staple of private equity. Early in a fund’s life, fees and costs outweigh returns, dragging metrics down. It’s only later, as investments mature and distributions accelerate, that the curve begins its upward climb.

The following chart illustrates the evolution of TVPI, DPI, and RVPI over time for BioVenture Fund I, showcasing the typical J-curve pattern:

Figure 1: The J-Curve for BioVenture Fund I demonstrates how early returns (DPI) lag while residual value (RVPI) initially dominates, eventually giving way to realized returns as the fund matures.

Sisko's Reality Check

Sisko plotted the fund’s performance metrics over time, creating a familiar J-curve:

$$

\text{TVPI at Year 2} = \frac{\text{Cumulative Distributions} + \text{Residual Value}}{\text{Paid-In Capital}} = \frac{10 + 140}{100} = 1.5x

$$

But Sisko knew better than to stop there. TVPI combined both realized and unrealized returns, with the latter—Residual Value (RVPI)—being particularly subjective.

The Self-Reporting Problem

The residual value that Sisko was so heavily relying on? Entirely self-reported. GPs have significant discretion in how they value their portfolios. A promising pipeline drug might be valued at $100 million based on optimistic projections of a 90% chance of success. But as Sisko discovered, the real probability was closer to 50%.

Adjusted RVPI

To account for uncertainty, Sisko recalculated RVPI using more realistic probabilities:

$$

\text{RVPI} = \frac{\text{Residual Value}}{\text{Paid-In Capital}}

$$

For a $100 million drug with a 50% chance of success:

$$

\text{Adjusted RVPI} = \frac{100 \times 0.5}{100} = 0.5x

$$

Suddenly, that stellar TVPI of 1.5x looked a lot less impressive.

Are These Metrics Used in Venture Capital?

Yes, the metrics TVPI, DPI, and RVPI are also used in venture capital (VC), albeit with some nuances. In VC, these metrics are often even more volatile due to the high-risk, high-reward nature of early-stage investments. For example:

- TVPI: Early-stage VCs rely heavily on TVPI to showcase potential returns since realized distributions (DPI) are rare during a fund’s early years.

- DPI: This becomes meaningful only when portfolio companies are successfully exited, often through IPOs or acquisitions.

- RVPI: Valuations in VC are often based on funding rounds, which can be optimistic or inflated, making RVPI particularly subjective.

While these metrics serve as important benchmarks in both PE and VC, their limitations—self-reporting, lack of discounting for time value, and reliance on projections—remain significant.

Time Value of Money: The Forgotten Factor

One of Sisko's favorite sayings was, “A dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow.” This foundational principle of finance—Time Value of Money (TVM)—is conspicuously absent from the private equity metrics of TVPI, DPI, and RVPI. These metrics treat all cash flows equally, whether they are returned in year one or year ten. This oversight can be particularly misleading in sectors like biotech, where long timelines are the norm, and investors may wait a decade or more for meaningful distributions.

Sisko, curious about the real economic value of his investment, decided to investigate further. By incorporating TVM, he aimed to determine whether the fund’s glowing TVPI of 1.5x truly reflected its performance—or was merely an artifact of delayed cash flows and inflated residual values.

Connecting the Metrics to TVM

Let’s revisit the three metrics to understand why they fall short in capturing the time-sensitive nature of returns:

TVPI, which combines the two, assumes that all returns—realized and unrealized—are equally valuable:

$$

\text{TVPI} = \text{DPI} + \text{RVPI}

$$

RVPI accounts for unrealized portfolio value but depends heavily on subjective valuations:

$$

\text{RVPI} = \frac{\text{Residual Value}}{\text{Paid-In Capital}}

$$

DPI reflects only realized distributions but ignores the timing of those distributions:

$$

\text{DPI} = \frac{\text{Cumulative Distributions}}{\text{Paid-In Capital}}

$$

While these metrics provide a snapshot of performance, they fail to recognize that $1 distributed today is more valuable than $1 distributed years from now.

Applying Discounting

Sisko recalculated TVPI using the Discounted TVPI formula, which adjusts for TVM by discounting future distributions and residual values to their present value:

$$

\text{Discounted TVPI} = \frac{\sum_{t=1}^{N} \frac{\text{Distributions}_t}{(1 + r)^t} + \frac{\text{Residual Value}}{(1 + r)^N}}{\text{Paid-In Capital}}

$$

Where:

- r = 8% (the discount rate)

- t = time period in years

- N = total duration of the fund

Cash Flow Timeline

| Year | Distributions ($M) | Residual Value ($M) | Discounted Value ($M) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 0 | 90 | 71.2 |

| 7 | 40 | 60 | 23.2 (distributions) |

| 10 | 90 | 10 | 4.6 (residual value) |

Sisko’s recalculated Discounted TVPI:

$$

\text{Discounted TVPI} = \frac{0 + 23.2 + 4.6}{100} \approx 0.28x

$$

Metrics Over Time: The J-Curve

At first glance, the fund’s TVPI seemed promising:

Year 3:

$$

\text{DPI} = 0, \quad \text{RVPI} = \frac{90}{100} = 0.9x, \quad \text{TVPI} = 0 + 0.9 = 0.9x

$$

Year 7:

$$

\text{DPI} = \frac{40}{100} = 0.4x, \quad \text{RVPI} = \frac{60}{100} = 0.6x, \quad \text{TVPI} = 0.4 + 0.6 = 1.0x

$$

Year 10:

$$

\text{DPI} = \frac{90}{100} = 0.9x, \quad \text{RVPI} = \frac{10}{100} = 0.1x, \quad \text{TVPI} = 0.9 + 0.1 = 1.0x

$$

However, these figures ignored the time delay inherent in the distributions.

The Conclusion

Sisko’s analysis revealed a harsh truth: The GP’s glowing TVPI of 1.5x was misleading. When adjusted for the time value of money, the actual economic return was a mere 0.28x. This adjustment underscores three key lessons for private equity and venture capital investors:

- Metrics are not gospel truths: TVPI, DPI, and RVPI are useful, but they oversimplify the complexities of return timing and valuation subjectivity.

- Discounting matters: Incorporating TVM reveals the true economic performance of investments, especially for long-horizon sectors like biotech.

- Skepticism is essential: Always dig deeper into the assumptions behind fund metrics, particularly when dealing with unrealized valuations.

For Sisko, this analysis was a reminder that a metric is only as reliable as the story it tells—and some stories are better left unpolished.

Member discussion